my january 2025 reads

book reviews, commonplacing, and my tendency to go overboard at the library.

Last October, I started the practice of keeping a commonplace notebook. I was very excited by the prospect after reading a number of posts, articles, and tips of why and how other people like to keep their own. I was motivated by a desire to remember and retain more of what I read, particularly considering the amount of books I like to borrow from the library. I would often find myself checking out a book, having lots of thoughts while I was reading, and if I didn’t record a review in my Goodreads (something I only do maybe 10% of the time), even a week later all my thoughts on the book had dissipated.1 Even with books I own, annotate, and keep on my shelves, I was finding that I was losing my immediate impressions of the book. Sure, I can open these books up at any time to see what I was scribbling in half-cursive in the margins, but the precise reason I was especially caught by a line, or the connections between themes across the book, or the spark that led me to annotate that passage—these wouldn’t strike me quite the same way as they did in that moment.

So I unearthed a fresh notebook I had been hoarding and set up my commonplace notebook. As for topics I thought to outline in advance, I chose thoughts on books, films & tv, and music; recipes, creative ideas, miscellaneous articles and references, quotes and inspiring tidbits, and people watching and observations of others. So far, the notebook primarily comprises literature thoughts, though I have a few entries on music and miscellaneous quotes. (For someone with two film degrees, I have been slacking in the cinephile department2, though I did log a long entry on RaMell Ross’s Nickel Boys, my personal pick for this year’s Best Picture Academy Award.)

In my first entry, dated October 19, I write:

I’m very excited to start this book! after watching a few videos about it, I was somewhat intrigued… then this morning while reading about Villette [by Charlotte Brontë] I screenshotted something I’d want to remember then realized I am constantly doing that, saving or screenshotting things I’ve read that I would like to remember but then… never going back to find them, so to the dying realm of my various digital folders they go (and remain). So what better place than one of these? I’ve read & thought so many cool things that I would love to be able to reference… plus I had this notebook sitting around calling my name. I’m excited to be able to chart my journey through the things I’m reading and invested in.

For some books, I record an entry when I’m part way through reading, especially if I learn or come across something I really want to avoid forgetting. Otherwise, I note the page number of quotes I like while I’m reading, and then will sit down with the notebook after I finish the book, record these quotes, and write any other thoughts that come to mind. In another early entry, I copied down a quote from Percival Everett, spoken during his reading event for James as part of the Living Writers series at Colgate University:

Reading really is subversive because no one can see what is going into you. They can look over your shoulder and see all the words you see, but they will never know what they mean to you.

I love this quote. This commonplace book, for me, is a way of recording what is “going into” me. Here is what has stuck with me through the past month of reading—this post is a way of, as I wrote to myself in October, charting my journey through the things I read and was invested in. I finished six books last month, as well as started seven others, six of which I’m currently reading.

this post will get cut off if you are reading in email. read on the app or web/desktop!

Seeing Red by Lina Meruane, 2012, translated into English by Megan McDowell, 2016

Billed as an autobiographical novel, Seeing Red by Chile’s Lina Meruane details the sufferings of a young Chilean writer living in New York who endures a stroke at the opening of the novel which causes a vessel in her eye to burst, rendering her blind. Meruane’s visceral, bitter narration explores the relationship between the body and emotions, uncertainty amidst dark times, the unknowability of anything beyond our own realm of experience, and states and methods of dysfunctional systems, distraction and futility, agency and repression, and longevity and impermanence.

“Because that was the only certainty, inaugurating our life with glasses washed by shadow, letting ourselves be stunned by the silence.”

I appreciate this book slightly more as a whole than I did while I was reading, though I was certainly blown away by much of the prose throughout, plus the final line took my breath away. I really enjoyed the lucidity of Meruane’s themes, and for a book which makes references to AIDS, the shadow of the Iraq War and the Twin Towers, and political conflicts and social problems in Chile, I thought the way these themes emerge by way of the primary plot—about the writer and her navigation of her blindness and operations attempting to reverse her condition—echoed these world events deftly.

The Little Friend by Donna Tartt, 2002

A theme with this month was books I appreciate holistically as works and can respect for what they are trying to do or accomplish, and think that they did or accomplished those aims well. But despite this, there are still reasons I didn’t completely mesh with the book, whether because I may not be the right reader for it, it might be the wrong time, or there’s some other barrier preventing me from totally connecting with the book. The Little Friend was one of these books.

Anyone who knows me knows the bond I formed with Tartt’s The Goldfinch when I read it in high school goes deep. It was one of the first books I read that resonated with me on so many levels. It came at an opportune time in my life and helped me understand grief in a way I really needed. I expounded on my love for that book in short-answer questions on my college apps, and in my undergraduate writing seminar I wrote an essay on why The Goldfinch resonated so deeply with me which was nominated for an award at my school. And with The Secret History, I did another school project, writing and proposing a creative treatment for a limited series adaptation of the novel. Needless to say, I admire Donna Tartt’s writing3, so I was really looking forward to filling this blind spot. Her second novel, The Little Friend follows Harriet, the youngest child of a white family living in Mississippi in the 1970s. When she was an infant, Harriet’s older brother Robin, at the age of 9, was found hanging from a tree in the family’s backyard. A decade later, Harriet seeks to uncover the vague circumstances of Robin’s death, a memory that her family has written over and repressed.

An important point to remember with this book, which I maybe wish I had known going in, is that while Harriet seeks to find and punish the perpetrator of Robin’s death, the novel itself does not. Informed by her reading of books like Treasure Island and The Jungle Book, Harriet sets out believing that children can go on swashbuckling adventures and emerge heroic. In her quest, she seeks answers and vindication, but the narrative has a different plan for her, that being her introduction into the adult world despite her young age. She witnesses violence, poverty, cruelty, hatred, and mayhem. She learns the adult world is more chaotic, less deterministic, and less benign than she thought. In her adventures, things go terribly wrong: people are hurt, love is lost, and nothing is solved. On these fronts, I really appreciate the novel for what it accomplishes. But I won’t lie and say I enjoyed the journey the whole way through. There were times this felt a chore to get through, and key characters with long chapters who I didn’t care to follow. I also felt slightly let down in what I thought would be, based on the opening of the novel, a crucial theme, that of the malleability and manipulation of memory. On Harriet’s family, from the prologue:

“[…] by group effort, they arrived together at a single song; a song which was then memorized, and sung by the entire company again and again, which slowly eroded memory and came to take the place of truth […] And—since this willful amnesia had kept Robin’s death from being translated into that sweet old family vernacular which smoothed even the bitterest mysteries into comfortable, comprehensible form—the memory of that day’s events had a chaotic, fragmented quality, bright mirror-shards of nightmare which flared at the smell of wisteria, the creaking of a clothes-line, a certain stormy cast of spring light.”

It’s no secret that Tartt’s prose, her rhythms and word choice, are incredibly evocative. The friend with whom I buddy-read this book, Julia, and I created a collaborative Pinterest board where we cataloged references and settings from the book, images that Tartt’s writing evokes, and more, and the board is chock-full of rich imagery. We wouldn’t have had such a clear picture of the world Tartt creates without the power of her writing. Nevertheless, there was something to be desired with this book, but I don’t want to take away from its merits.

The Princess of 72nd Street by Elaine Kraf, 1979

Another case of appreciation for what Kraf accomplishes, though I still feel at a distance from the novel as a reader. Kraf’s “underappreciated classic” is written from the perspective of Ellen, a writer and painter like Kraf herself, living on New York’s Upper West Side. Occasionally undergoing manic episodes, which she calls “radiances” and under which she transforms into the glorious and liberated Princess Esmeralda presiding over the realm spanning 72nd Street between Central Park West and Riverside Park4, Ellen describes what she experiences during, and as a result of, her seventh radiance. The dreamy quality of Kraf’s prose and flows of the narrative really capture the headspace of her character.

Ellen loves her radiances. During them, she floats and dances happily, her hands turn into flowers, joy seeps from her cells. She much prefers embracing the radiances over when others try to “treat this lovely feeling with drugs.” Ex-boyfriends insist upon her hospitalization, doctors forcibly minister drugs that numb her limbs and stupefy her mind, or she is arrested: “I can be easily arrested during radiance because according to law and order I am out of order.” Under these drugs, Ellen says, “I cannot laugh suddenly or cry or even dance. It is like something is binding me. But I can follow orders very well. I can do whatever I am told.” This time, during radiance seven, she decides to write reminders to herself—codes of conduct to follow during this radiance, like “DON’T LET STRANGE MEN INTO THE APARTMENT” and “MONEY IS THE MEANS OF BARTER”—and even goes so far as to tie a system of ropes to avoid leaving her apartment in her state of lowered inhibitions. During her radiances, she is incapable of feeling pain.

As she descends—or, as Ellen might have thought, ascends—deeper into her radiance, she experiences lapses in memory and comes out the other side with physical reminders of what happened in the interim, which she then has to piece together. These lapses are employed to a melancholy effect, contrasting with the colorful, joyful, sensational mood Ellen feels at the beginnings of radiances.

“I must always live here where the sun blooms and the water is purple and the streets are soft and the sun blows love upon both of you and the red meat sizzles on flames so I am not myself as you know me but part of the flame of the sun which is also on the flame-shaped blade of grass, I said.”

Coupled with her self-assured set of morals and opinions on gender roles and womanhood, Ellen’s is a radical voice and she resents when her liberated self is repressed by the orders of society. She sees her morality as ruled by “the highest ideals of love, kindness, and felicity to one’s mate”. Kraf’s novel is at the same time glowing and gritty. While I didn’t always relish my time reading this, the more time it has to sink in, the more of an impression it leaves on me. I finished typing this review with a deep appreciation for what Kraf has created, more so than I did when I started writing.

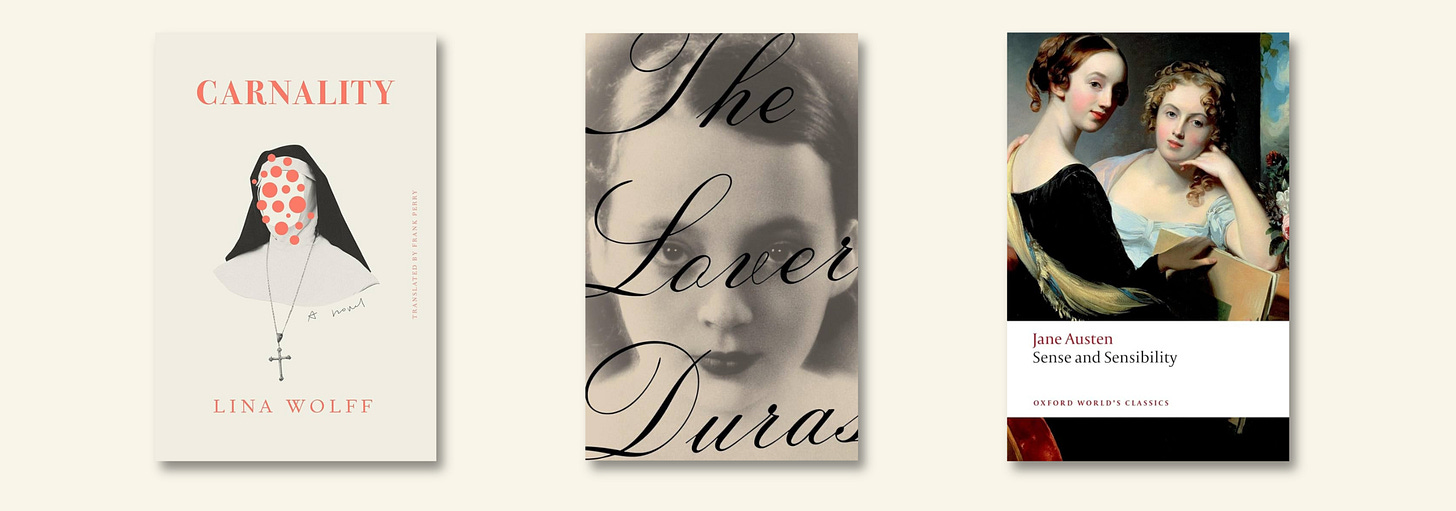

Carnality by Lina Wolff, 2019, translated into English by Frank Perry, 2022

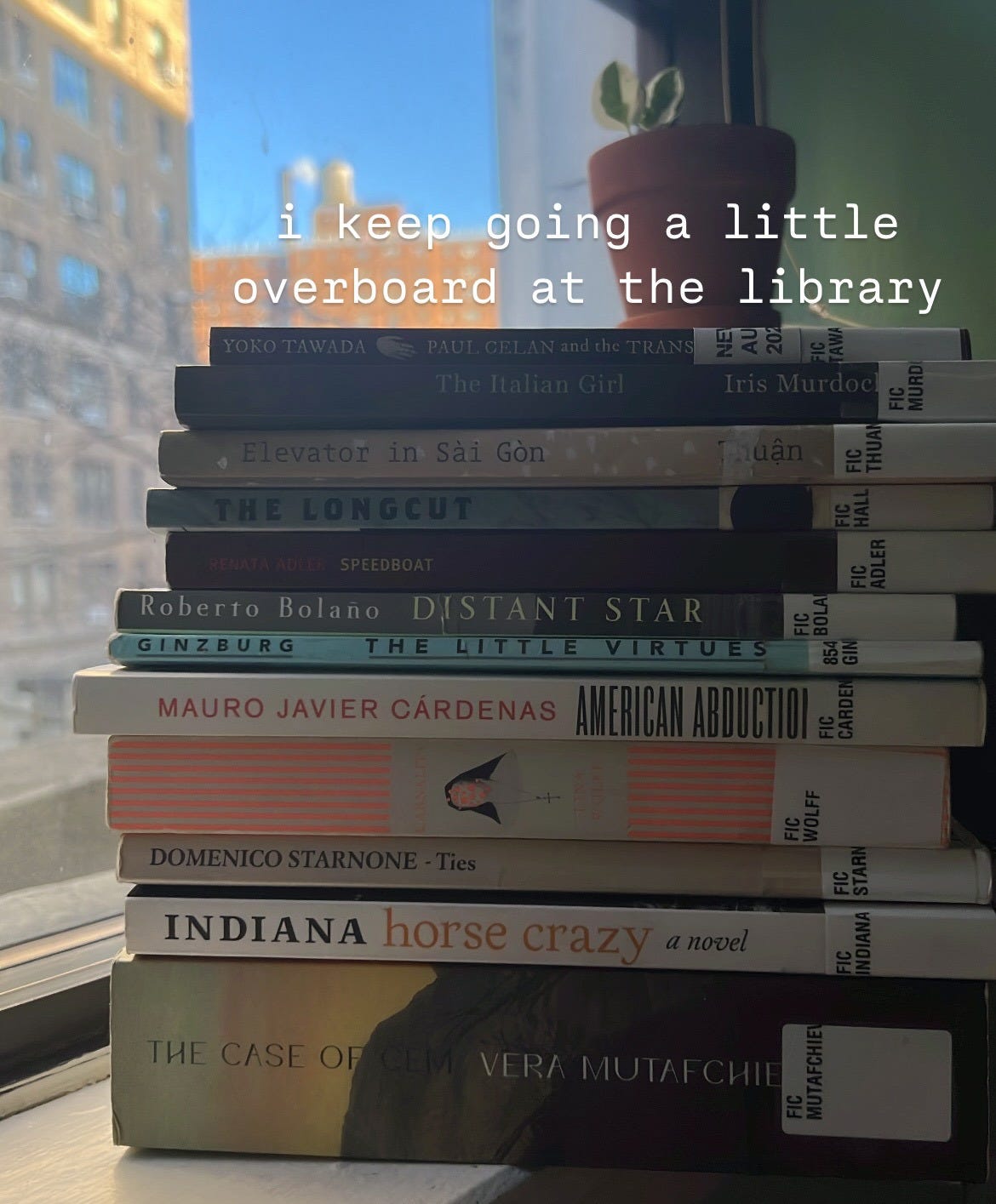

I grabbed this at the library when I went to pick up The Princess of 72nd Street and left with four additional books that caught my eye after perusing the stacks. This is another recurring theme this month. The only consolation is that the books I’m checking out are not highly-requested at the library so I have virtually unlimited renewals. We’ll see what I actually get around to polishing off of this stack.

My first novel translated from Swedish, Lina Wolff’s Carnality—originally titled Köttets tid in Swedish, which according to Google Translate means “The Time of the Flesh” and is a very cool title—is kind of the quintessential 3½ ⭑ book in my personal ratings system. Divided into three large sections, each devoted to a different character’s perspective, Carnality follows Swedish writer Bennedith, who visits Madrid for a writing residency and meets a Spanish man named Mercuro, who is grieving his infidelity to his wife and a recent experience that has left him shaken and seeking Bennedith’s help. When Mercuro opens up about this experience, we are plunged into a seedy underbelly centered around a restricted-access internet TV show funded by cryptocurrency investments, where contestants with problems come in times of desperation, authorizing the minds behind the TV show—including an aging nun named Lucia who bubbles with inner turmoil—to enact whatever drastic means they see fit in order to solve these problems. With a live-feed comments section teeming with hate and mirth at witnessing the utter humiliation of people they deem deserving of it, the TV show speaks to society’s need for a pessimistic outlet, where one can witness the depths of human despair and revel in the degradation of morality.

This is an interesting premise, but the bulk of the novel comprises exposition of how Mercuro found himself on the show—and his subsequent paranoia as he attempts to escape the plan its creators have laid out for him—and an extended epistolary section in which the nun Lucia writes to Bennedith, explaining her point of view against Mercuro’s and detailing her childhood and how it led to the creation of this TV show. While its promised themes, on nihilism, punishment, and morality, are compelling and the unfolding of events is propulsive, I think ultimately this under-delivered for me. Still a solid novel, though.

“We always talk about the system from the perspective of the individual and never about the individual from the perspective of the system. From the perspective of the system the individual is always organic and desperately in need. From the perspective of the system the individual has always just bashed his thumb with a big hammer and requires assistance. The truth is, though, that the individual is an ant, and no one is going to bring an entire system to a halt just to relieve the completely insignificant pain of one ant.”

The Lover by Marguerite Duras, 1984, translated into English by Barbara Bray, 1986

Read this with my boyfriend Dylan, the sixth book we’ve read together as part of our intermittent book club. In the past we’ve read Dune, Madame Bovary5, Babel, Stoner, and The Haunting of Hill House. French novelist, screenwriter, playwright, essayist, and filmmaker Marguerite Duras’s autobiographical novel follows an unnamed 15-year-old French girl going between her family’s home in Sa Dec and her boarding school in Saigon in 1929 French Indochina. She meets a Chinese man 12 years her senior, the son of a wealthy businessman, and the two begin an affair.

The daughter of a French school teacher, Duras/the girl is part of the class of poor French living in the colony. Her proximity to the rich Chinese man affords her and her family luxuries they would never ordinarily have access to, drawn particularly in a scene where the man meets the girl’s mother and older brothers for the first time and brings them to an expensive Chinese restaurant. The family feast ravenously and thanklessly, never acknowledging the man’s presence or speaking to or about him at all. The girl is ashamed of her family’s conduct but still doesn’t go so far as to reprimand them in defense of her lover. This tension, stemming from the family’s status at the bottom of the class of colonizers due to their poverty, while enjoying being beneficiaries of the man’s wealth yet disdaining his being racially other, was very interesting to me.

Duras’s writing is lovely in its melancholic mystique. I liked letting the vignettes and cyclical narration wash over me, but I knew I wasn’t quite grasping all the formal depth—I sense there’s much more that frankly went just over my head, namely in the ways that Duras renders these different shades of otherness and boundarylessness. The narrator writes of her affair from the distance of many decades, and we see how she holds within herself all the different versions of her past selves. This is very clearly an influence on Annie Ernaux’s style, and made me want to read more from both writers.

“I feel a sadness I expected and which comes only from myself. I say I’ve always been sad. That I can see the same sadness in photos of myself when I was small. That today, recognizing it as the sadness I’ve always had, I could almost call it by my own name, it’s so like me.”

Interestingly, Dylan had read Duras’s My Cinema which compiles reflections from Duras on her writing and filmmaking practices, and shared that Duras has distanced herself from The Lover (L’Amant) as a work. In a 1991 interview, referring to Jean-Jacques Annaud’s then-forthcoming film adaptation of The Lover which was released in 1992, Duras says,

It’s in his hands[…] The film will have nothing to do with L’Amant de la Chine du Nord, which is now the real L’Amant for me. I wrote four screenplays based on the first book, on L’Amant, in order to regain my freedom.

The novel, L’Amant de la Chine du Nord, was first published in English in 1992 as The North China Lover, translated by Leigh Hafrey. When asked if she feels “dispossessed of” the original book, she also says, “You can’t take it away from me, but I did take it back. I took it back, that’s true. I started all over again, and from the very beginning. As if it were the first time.” She considers L’Amant de la Chine du Nord a “reappropriation” and notes that another major difference between the two books is that between them, she learned of the death of the Chinese lover whom the character is based on. That Duras considers this novel to be “the real L’Amant” makes me curious to see how it differs in order to understand her rejection of L’Amant better. And based on Duras’s lukewarm opinion of Annaud’s adaptation—she says she authorized the adaptation really only for the money, she didn’t approve of the actress chosen to play the girl, who she thought was too pretty (“If the little girl is too pretty, she won’t look at anything, she’ll let herself be looked at,” Duras wrote in her notebook), and she would have liked another director, Claude Berri, to have made an adaptation—I don’t think I’m likely to watch it, even though it stars Tony Leung.

Sense & Sensibility by Jane Austen

My third Austen novel, following Pride & Prejudice and Emma. This is a great novel, don’t get me wrong, but reading this after recently finishing Emma leaves something to be desired. Sense & Sensibility, Austen’s first novel, does what Austen does well—delivers twisty plotlines, obscures character motives until they’re ripe for maximum drama, and unfolds its narrative delightfully—and you can clearly see the groundwork for Austen’s future works; her common themes surrounding the society and morals of the time, the archetypes she likes to reach for, and that characteristic biting wit and satire are all here. I also felt very deeply for the characters, Marianne and Elinor Dashwood, in their journeys to find love in Devonshire. I sympathized with their pains and happinesses and enjoyed the fruits of their growth by the end—especially Marianne, who I think is afforded the opportunity to grow more.

“I considered the past; I saw in my own behaviour since the beginning of our acquaintance with him last autumn, nothing but a series of impudence towards myself, and want of kindness to others. I saw that my own feelings had prepared my sufferings, and that my want of fortitude under them had almost led me to the grave.”

But (can I say this?) I liked the film adaptation (Ang Lee’s 1995 version) more. I watched the film with Dylan and his brother before I read the book, and we had a blast, trying to figure out who was deceiving who and for what reasons, sharing theories like it was a mystery film. I don’t think watching an adaptation before reading a book is the crime my mom makes it out to be. “How can you read the book knowing everything that happens!” she cries. But I was very familiar with other Austen adaptations before reading the source material: I’ve watched Pride & Prejudice (2005, Joe Wright) and Emma (2020, Autumn de Wilde), and before seeing Emma I had seen Clueless (1995, Amy Heckerling) at least ten times.6 In fact, watching those adaptations is what made me want to read the books. The same is true with Anna Karenina. I had had only a vague inclination to read Tolstoy’s tome based solely on a duty to read the great classics. But I had picked it up in bookstores, read the first page, and been like, “No thanks.” Then after watching Joe Wright’s 2012 adaptation I thought, “That was amazing, I need to read the book ASAP.” I admit, after reading Sense & Sensibility, that there are a number of creative liberties that Lee and screenwriter-star Emma Thompson (in her first screenwriting role!) take in order to make the story more filmable—making things to characterize the cast happen onscreen rather than in description or hearsay about reputations or manners—I thought these changes worked very well in service of the drama.

This could also be my being at a remove as a modern reader, but I found Willoughby’s behavior totally inexcusable, even after his extensive apology after which the Dashwood sisters forgave him honorably. I found Edward to be flat and actionless and was surprised at how well he and Elinor apparently got along, because we see little of that in the novel, instead learning about him primarily through Elinor’s expounding on his virtues. And if not for Alan Rickman’s portrayal carrying my perception of Colonel Brandon, plus the additions the film made to rationalize the romance of his and Marianne’s relationship, I wouldn’t be totally sold on that character either.

Especially after reading A. Natasha Joukovsky’s excellent “Austen Math” series, particularly the installment on Emma, I felt even more strongly convicted of the strengths of Emma over Sense & Sensibility. That I’m comparing Austen’s first with her last-published novel is not lost on me, but I love my girl Emma Woodhouse (handsome, clever, and rich…) and really enjoyed the variety and complexity of characters and the juicy drama of Emma more than I enjoyed reading Sense & Sensibility. In any case, I love the challenge of reading Austen and look forward to reading her other works. The merits of this novel are incredibly strong, and comparing it to Emma is perhaps unfair. Still, I stand by my preference.

I would love to get in the practice of writing these monthly wrap-ups consistently. I really enjoyed synthesizing my thoughts in this piece, and the idea that another reader might come across something to add to their own TBR or read an alternative perspective on a book they liked or didn’t like makes me smile. This post is indebted to my commonplace notebook, without which I wouldn’t have recorded the quotes that stood out to me that I chose to highlight here. In my next post, I’ll share the myriad ways I keep track of my reading across different mediums and formats, and my reading intentions for the year—because I’m always nosy about how other people organize their reading systems.

To cap things off, here’s a quick-hits list of books I started in January and am still reading, and much briefer blurbs on my thoughts so far.

The Case of Cem by Vera Mutafchieva — This 1966 Bulgarian novel by historian Vera Mutafchieva, in its first English translation by Angela Rodel, is a thick volume about Cem, the educated son of a fallen Ottoman Sultan in the year 1481. It’s told in the style of court depositions from the perspective of various historical figures who knew/knew of, interacted or strategized with (or against) Cem, but we never hear from Cem himself. I’m liking this so far and learning a lot about the Ottoman Empire. I have to be in the right mood for it, though. I’m 39% through so far.

The Longcut by Emily Hall — This 2022 Dalkey Archive Press release is a doozy so far. I only recently realized why it is called The Longcut: because the narrator, an artist with an office job, is taking us on the opposite of a shortcut as she tries to get to the bottom of what her art is. (I feel that.) Hall’s meandering syntax can be challenging, but I’m trying not to get hung up on every turn of phrase I don’t quite follow. It’s a short but tough read. I’m 33% through.

Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk — The next book club pick I’m reading with Dylan. Isn’t this cover art (for the e-book version I’m reading, from Australian independent publisher Text Publishing) stunning? I’m 42% through and really enjoying it so far, but paused while we each read other books for now.

The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron — The Artist’s Way is having a moment right now. I had heard of the book years ago, but I was prompted to start after reading the installment of Petya K. Grady’s wonderful interview series, about what people she admires are reading, in which she interviews Celine Nguyen. I always enjoy reading Celine’s essays on topics including architecture, design, literature, and her research, pitching, reviewing, and writing process. In Petya’s interview, Celine expressed her high esteem for Cameron’s renowned book, which led me to download the book myself. Then, after going on a deep dive of Doechii last week (now a Grammy-awarded artist🥹), I immediately began admiring her. Her mixtape, Alligator Bites Never Heal, is absolutely incredible, and it’s clear how confident, driven, and intentional she is with her art. She is so exciting to follow. I learned that she, too, had her life changed via The Artist’s Way, so I finally started my own journey with the book. I’ve only read the first few sections but I’ve been doing Morning Pages for just over a week now. I’m 15%.

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy — Reading this with my mom! We read Jane Eyre last year and loved it. I will also be following Henry Eliot’s yearlong read of the book; though I am not personally planning on prolonging my reading time over 14 months, I still look forward to checking in on Eliot’s posts for the historical context and analysis he provides. In one of my discussions with my mom about it so far, she asked if we should watch the movie adaptation ten minutes at a time as an accompaniment to our reading. I thought that was a silly idea. And when I told her I have seen the movie (and loved it), she thought I was the weird one for reading a book in which I already know everything that happens. I’m 8% through and loving it.

The Idiot by Elif Batuman (re-read) — I read this digitally last year and adored it so much that I had to buy my own paperback copy. I’m re-reading to note all my digital annotations and to prepare for reading the second book, Either/Or, in Batuman’s “Selin Novels” series. I read that the third installment is called Camino Real! I’m 13% through this re-read.

A preview of February reads:

The Heart’s Invisible Furies by John Boyne — Read this for a book club pick with Dylan’s sisters. A very engrossing read, finished on the 1st of February, and I’m excited to discuss with them!

Plus any combination of the current reads above, and anything I get around to from this immense stack from the library… I keep going for one or two things and leave with an exponential amount more.

I’d love to hear your thoughts — any books here you’ve enjoyed or disliked? Thoughts on the library stack or your own love for the library? Do you have a commonplace book or would like to start one? Strong opinions about watching book adaptations? Or anything that comes to mind… Thank you for reading! Till next time.

At least part of this is due to the fact that I read a decent number of contemporary general fiction novels last year—many of which were disappointing. I’m not up in arms about the fact that I retained little of these in my long-term memory, but I disliked that in general I was losing my own thoughts and opinions along with the memory of the books.

I’ve just been more focused on reading this past year-plus, and between reading, job apps, and watching NY Knicks games every few evenings a week there’s only so much I can devote my attention to!

Tartt is known for releasing her novels around ten years apart. It’s been over ten years since The Goldfinch’s publication, and along with everyone else eagerly awaiting her next release, I hope there’s an announcement soon.

My favorite of the two parks.

I failed this book club round because Dylan read it from July to September, while I only started reading in September and picked it up and put it down over the next five months. I wish I had read it in one stint, as I still feel like there’s a lot I missed by leaving it by the wayside, reading other books, and coming back.

I was so familiar with Clueless while somehow not knowing, or forgetting, that it was based on Emma; I think I misremembered that Clueless was based on Taming of the Shrew. While Dylan and I were watching Emma for the first time, we had even re-watched Clueless not long before, and halfway through Emma we were both like, “Okay why is this just like Clueless…”